On the Road with “The Crooked Mirror”

After so many years of sitting alone in a room writing, reflecting… it’s fascinating to be out in the world with The Crooked Mirror. Who are its readers? Who was drawn to hear me talk about the book in Queens,NY, in San Francisco, in Los Angeles, Manhattan, Portland and Seattle? Some were old friends, appearing from various chapters of my life. Some were family– cousins with links to the story. Others saw an ad or heard a plug on the radio. Some came because they are intrigued, some because they were skeptical of the very premise: Polish-Jewish reconciliation.

At the Queens Jewish Library last month, there were many Jewish survivors of the camps in the crowded community room. One man rolled up his sleeve to show me the Auschwitz number tattooed on his arm, without comment. During my talk, these elders nodded their heads vigorously when I mentioned how, when Cheryl’s father came home after the war from the Soviet Union to his town of Kolomyja, where his neighbors shot at him. But they also listened attentively to stories of kindness, rescue, and the hard-won path towards reconciliation.

At USC, I gave a talk to students in the Masters in Professional Writing program. Two writing students– both working on memoirs about their African-American families– approached me afterwards, to say they’d taken inspiration from my tale. One of them owned to the dead-ends she’d encountered in the search for the history of her own family, from the time of slavery. “What do I do about all the gaps, the ragged edges?” she asked me sadly. Use them! I advised. Those holes in a family narrative are part of the story that has been obscured by time, emigration, and trauma.

At the NYU bookstore, I met Jack Malinowski, from Philadelphia, retired from 35 years with the American Friends Service Committee. Jack is the grandson of Poles– miners who emigrated from the Suwalki area of Poland in the late 1800’s. He grew up in a largely Polish Catholic community, near Shenandoah, Pa. “My parents were active in Polish American cultural activities,” he told me, “mostly on a Roman Catholic level. The synagogue in our town was near our house, but we mainly co-existed rather than mixed.” His father played a strong role helping DP’s after the war, and joined numerous Polish American voters leaving the Democratic party after Yalta (feeling betrayed by Roosevelt). In The Crooked Mirror, he said, “I found a rare and meaningful encounter.”

Tova Ofman is the daughter of Berek Ofman, a survivor from my family’s town of Radomsko, who is featured in the book. She flew in from Cleveland, bringing her two daughters so that they could hear a story that their grandfather had never told them. “I think he found it easier to tell his story to someone outside the family,” one of the lovely granddaughters thoughtfully observed.

I was delighted that my friend Sheku Mansaray could be in the audience at the New York Public Library. Sheku suffered through the atrocities of the civil war in Sierra Leone, losing both his parents and his arms to rebel soldiers. He sat beside storyteller Laura Simms, who wrote afterwards: “Sheku, like my son Ishmael, was a victim of a long civil war in Sierra Leone. Unlike Ishmael he did not become a soldier, but rather was scarred forever by a child soldier. A boy that he knew as a child from the next village. It was an amazing evening listening to tales of reconciliation after war, seated beside Sheku who is making some reconciliation within himself after the war.”

In many cities, people came up to me afterwards to tell me their family stories, to talk about their own searches to reconnect with history and lineage. In Portland, my friend Aron told me he was now going to search out the story of his grandmother Anne, who was one of the children on the Kindertransport. In San Francisco, I met Elizabeth Rynecki, who maintains a “virtual museum” and is producing a documentary film about her great-grandfather Moshe Rynecki, a renowned Warsaw painter (and a very fine one at that), who died in Majdanek. Moshe Rynecki’s son, George, Elizabeth’s grandfather, recovered over 100 of his father’s paintings, secreted away during the war. Elizabeth wrote this thoughtful response to The Crooked Mirror and posted it on her blog. I share it here.

Thanks to everyone who’s helped launch The Crooked Mirror out into the world. I also promise– in response to feedback– to post more pictures and a map in due time…

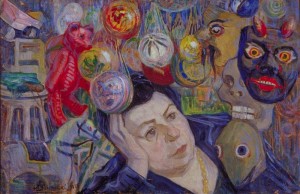

painting at top:

“Perla” by Moshe Rynecki, 1929.

December 8, 2013 at 2:24 pm

Thanks for the new post. I must, I must–and I will–lend your book to the friend who walked out of the Warsaw ghetto with his mother and never saw his father or sister again. – Laura

LikeLike

December 8, 2013 at 2:27 pm

I am still reading The Crooked Mirror. Every night, I find myself transported to a place I I’ve never been with people I don’t know. And yet it’s all strangely familiar. It’s an emotional adventure.

>

LikeLike

December 9, 2013 at 7:55 am

I’ve been so moved by “The Crooked Mirror.” It parallels some of what I discovered in nearby Lithuania, where I went in search of my Jewish family story — and ended up exploring how Lithuania is encountering *its* Jewish heritage. (My book, “We Are Here: Memoirs of the Lithuanian Holocaust” tells the tale.) Thanks so much, Louise.

LikeLike